Michael Mosley’s Horizon documentary – The Placebo Experiment: Can My Brain Cure My Body? – was shown this month on BBC2.

In brief, for those who haven’t watched the programme, over 100 chronic back pain sufferers were gathered together to take part in clinical trials of a new painkiller. Unbeknown to them, there were no pain-killing constituents in their blue and white capsules: yet 45 per cent of participants who received the ground rice tablets reported their pain symptoms had improved.

Placebo is a Latin word meaning ‘I shall please’. It appears to have entered medical terminology in the 18th century. You pays your money and you takes your choice: some credit Royal Naval doctor James Lind (1716-94) with its inception, while others name Scottish physician and pharmacologist William Cullen (1710-90).

While there may not have been a specific name assigned to the powerful effect of belief prior to the 18th century, one suspects the placebo effect has been practised since the beginning of time: is there one among us whose bumped head or grazed knee wasn’t ‘kissed better’ when we were children – and who hasn’t rubbed a nettle sting vigorously with a dock leaf?

I’ve arrived at the conclusion colourful Elastoplasts with cartoon characters beat ordinary ones hands-down when dealing with grandchildren’s small cuts and scrapes.

Hands-up who remembers The Scaffold’s catchy song lyrics Let’s drink to Lily the Pink – most efficacious in every way?

Sixty years ago when I was the-child-of-the-surgery with the medical dispensary the other side of our kitchen door it was not uncommon to occasionally see repeat coloured sugar water prescriptions set out for collection labelled ‘Tonic.’

Post-war, when the offerings of the medical pharmaceutical industry were considerably less than now, coloured water or sugar pills were sometimes prescribed when patients believed this ‘medication’ was efficacious but where there was no apparent underlying medical symptom requiring specific medicine.

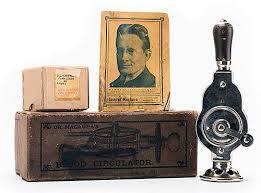

Father’s brother Clifford died earlier this year. He owned an extraordinary machine by the name of Macaura’s Blood Circulator (circa 1900) guaranteed to delight children because of its noisiness.

Instructions issued with the blood circulator claimed relief from symptoms such as asthma, deafness, heart disease, anaemia, and ‘women’s problems’. Looking a bit like an old fashioned egg whisk – with a circular pad where you’d otherwise expect to find the whisk – on cranking the handle and applying the disc to the body 2,000 vibrations per minute were produced/received.

Post-war, when my uncle qualified in medicine, these machines were still sometimes used in general practice to treat back pain where all else failed… which interested me: after a strenuous day’s gardening my husband or I might plug in our electric back massager which delivers a ‘shiatsu-type’ massage as its rollers glide and vibrate up and down the spine.

The Macaura Circulator made a noise rather like a machine gun – which might explain why uncle’s grandchildren enjoyed playing with it.

Latterly he discovered a few spins of the handle scared away the wood pigeons from their garden – which pleased my aunt no end, because the pigeons ate food she put out for garden birds.

By the way, Dr Macaura was sent to jail for three years in France for ‘swindling’ in 1914.

His vibratory machine didn’t live up to the claims made for it.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here